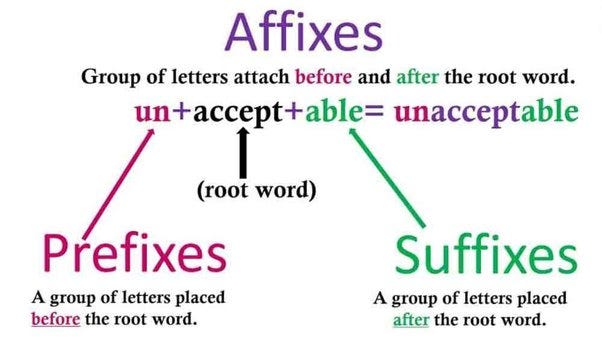

Do you ever feel confused? Most people are familiar with this common adjective; they could answer the question with ease. The adjective disoriented is somewhat less common in everyday speech. Disoriented and confused carry similar meanings, but disoriented may be less familiar for some folks. A brief study of prefixes and suffixes, known collectively as affixes, can often help you decode just about any challenging word. Let’s start with the prefix in the word disoriented!

Prefixes

Prefixes come at the beginning of a word. They are usually one to three letters long, and attaching them to a word will affect the word’s meaning. Some prefixes even combine with other prefixes to create words such as unpremeditated (un+ pre+ meditated).

The Negative Nellies

Dis- means not, absence of, apart, away, or having a reversing force. Since dis- means not, what does disoriented mean? It’s pretty simple when you know the prefix.

Mis- and mal- mean wrong or bad and are sometimes used for negation. Besides the common mistake, these prefixes also introduce the words misaligned, misfit, malformed, and malfunction.

Im- and its variant in- mean not. Think impossible, impregnable, incapable, inconceivable.

Un- also means not. It is a very common prefix seen in words such as unstoppable, unconquered, and unrestrained. In fact, there are quite a few prefixes that mean not. Don’t forget il- as in illogical and ir- as in irreversible.

The Overachievers

Extra- is not just a brand of gum. As a prefix, it means beyond. Extraterrestrials live beyond the boundaries of our earth. Extrasensory perception refers to receiving information beyond what your senses would normally detect.

Superman illustrates the prefix super- to a tee. Didn’t he go above and beyond to save lives?

The Weights and Balances

Lots of prefixes clue us in on size. Especially large things are described with prefixes like mega- and macro- while small things are micro- or mini-. That information can help you to buy electronics: Would you prefer a minicomputer or one with more megabytes?

Equi- means equal, as in equidistant. The semi- of semigloss paint lets you know that it is only partially glossy.

Other prefixes indicate quantity like over- (excess) and under- (insufficiency).

The Counters

Prefixes can tell you how much of something there is. Mono- and uni- mean one. How many wheels does a unicycle have? How many people speak during a monologue? Bi- and di- refer to two. For a comprehensive list of numerical prefixes, visit Factmonster.com.

The GPS Prefixes

If you like to know where things are, you will appreciate the following group of prefixes. They designate locations. You can remember them by associating them with common examples. Submarines go under the water. Transporters carry goods across distances from one place to another. The infrastructure is the basic framework underlying an organization. Peripheral vision helps you to see around yourself.

Straitlaced Prefixes

These prefixes involve time and order. Difficult words like antecedent and precedent are simpler to decode if you remember that ante- and pre- mean before.

Post- means after. Retro- signifies backward. Prim(e)- denotes first.

Suffixes

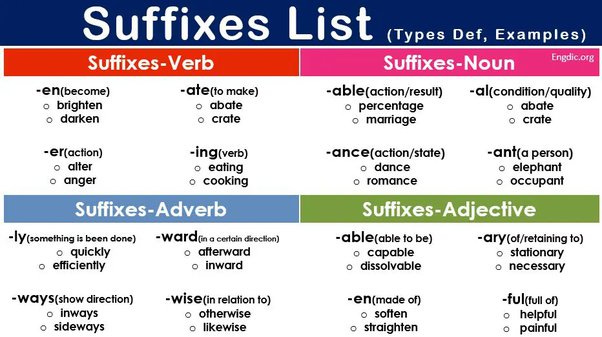

You find suffixes at the ends of words. Like prefixes, they are a rich source of information about a word. Have you ever seen blue or pink balloons at a baby shower? Some parents use colors to indicate the sex of their new baby. In the same way, some suffixes announce what part of speech a word is. Here are some examples.

“It’s a Noun”

The following suffixes are usually found at the end of nouns: -ance, -ation, -ness, -ism, -ment, -ship.

Beyond giving clues to the part of speech, suffixes also carry meaning. The endings -er, -or, -ist, or -yst are commonly added to words for people who perform certain tasks or activities. Examples include programmer, calculator, analyst, and abolitionist.

“It’s a Verb”

There are several suffixes associated with the meaning to make. By combining the baseactive with the suffix -ate, you create the word activate, which means to make active.

Other suffixes with this meaning are -ize, -ise, -ify, and -en. What verbs do you know that end with these suffixes?

“It’s an Adverb”

In the majority of cases, adverbs are formed by adding -ly to an adjective. For instance, beautiful becomes beautifully. If the adjective already ends with a y as in easy, you would replace the y with -ily to form the adverb easily. There is a special rule for adjectives ending in -able, -ible, or -le: replace the -e with -y. For most words ending in -ic (with the exception of public) add -ally.

“It’s an Adjective”

Brownish is a color strongly reminiscent of brown, but not quite brown. People have a lot of fun with -ish because it means similar. You may even hear someone use this suffix alone in response to a question. Sally and Peter are dating, aren’t they? …Ish! The slang use of the suffix means “something like that.”

-Al, -ar, -ed, -ic, -ical, and -ive signify having the quality of. Magnetic objects, for example, have qualities of magnets.

The -ous of dangerous means full of or like, while -less means without.

Do you ever feel disoriented, unhinged, or disarranged? If you used hints from the prefixes and suffixes in these words, you realized that they are synonyms of disoriented. Next time you encounter a tough word, don’t panic. Use those little building blocks to guess the meaning of the term.