The Conversation explores how tools like ChatGPT are subtly reshaping the way we write. While these tools can save time and improve clarity, they can also smooth out our quirks and dilute our voice. As the author wisely notes, “writing should be about expressing your ideas in your own way.”

Have you noticed certain words and phrases popping up everywhere lately?

Phrases such as “delve into” and “navigate the landscape” seem to feature in everything from social media posts to news articles and academic publications. They may sound fancy, but their overuse can make a text feel monotonous and repetitive.

This trend may be linked to the increasing use of generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools such as ChatGPT and other large language models (LLMs). These tools are designed to make writing easier by offering suggestions based on patterns in the text they were trained on.

However, these patterns can lead to the overuse of certain stylistic words and phrases, resulting in works that don’t closely resemble genuine human writing.

The rise of stylistic language

Generative AI tools are trained on vast amounts of text from various sources. As such, they tend to favour the most common words and phrases in their outputs.

Since ChatGPT’s release, the use of words such as “delves”, “showcasing”, “underscores”, “pivotal”, “realm” and “meticulous” has surged in academic writing.

And although most of the research has looked specifically at academic writing, the stylistic language trend has appeared in various other forms of writing, including student essays and school applications. As one editor told Forbes, “tapestry” is a particularly common offending term in cases where AI was used to write a draft:

I no longer believe there’s a way to innocently use the word ‘tapestry’ in an essay; if the word ‘tapestry’ appears, it was generated by ChatGPT.

Why it’s a problem

The overuse of certain words and phrases leads to writing losing its personal touch. It becomes harder to distinguish between individual voices and perspectives and everything takes on a robotic undertone.

Also, words such as “revolutionise” or “intriguing” – while they might seem like they’re giving you a more polished product – can actually make writing harder to understand.

Stylish and/or flowery language doesn’t communicate ideas as effectively as clear and straightforward language. Beyond this, one study found simple and precise words not only enhance comprehension, but also make the writer appear more intelligent.

Lastly, the overuse of stylistic words can make writing boring. Writing should be engaging and varied; relying on a few buzzwords will lead to readers tuning out.

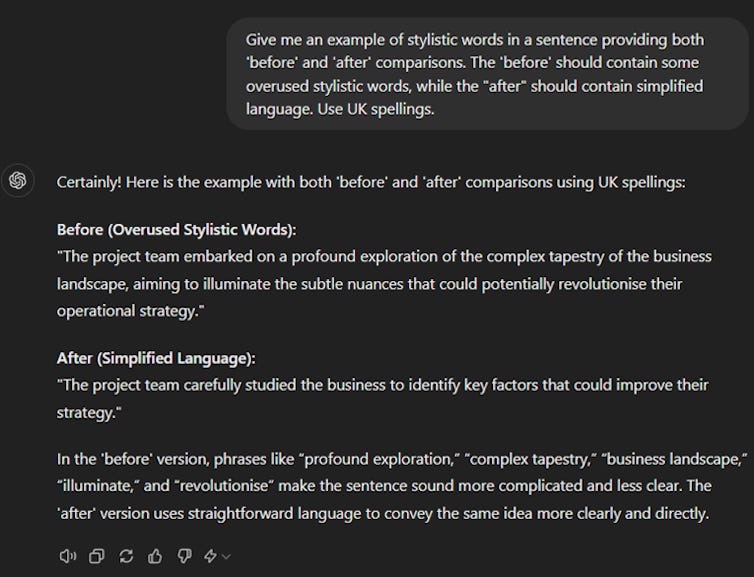

There’s currently no research that can give us an exact list of the most common stylistic words used by ChatGPT; this would require an exhaustive analysis of every output ever generated. That said, here’s what ChatGPT itself presented when asked the question.

Possible solutions

So how can we fix this? Here are some ideas:

1. Be aware of repetition

If you’re using a tool such as ChatGPT, pay attention to how often certain words or phrases come up. If you notice the same terms appearing again and again, try switching them out for simpler and/or more original language. Instead of saying “delve into” you could just say “explore”, or “look at it closely”.

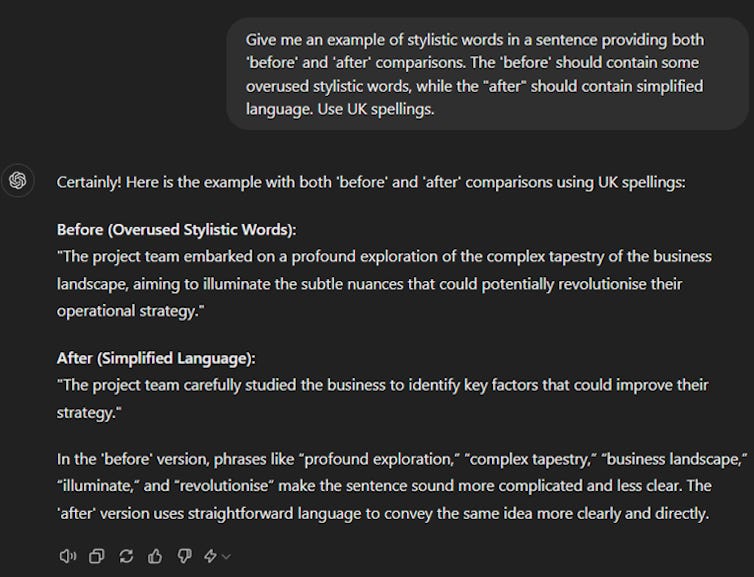

2. Ask for clear language

Much of what you get out of ChatGPT will come down to the specific prompt you give it. If you don’t want complex language, try asking it to “write clearly, without using complex words”.

3. Edit your work

ChatGPT can be a helpful starting point for writing many different types of text, but editing its outputs remains important. By reviewing and changing certain words and phrases, you can still add your own voice to the output.

Being creative with synonyms is one way to do this. You could use a thesaurus, or think more carefully about what you’re trying to communicate in your text – and how you might do this in a new way.

4. Customise AI settings

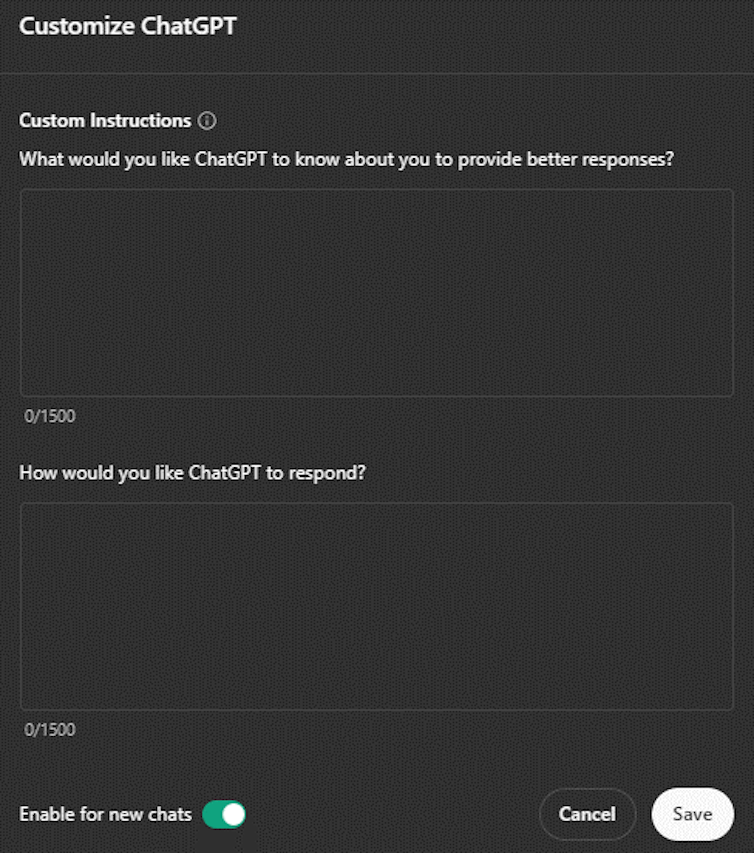

Many AI tools such as ChatGPT, Microsoft Copilot and Claude allow you to adjust the writing style through settings or tailored prompts. For example, you can prioritise clarity and simplicity, or create an exclusion list to avoid certain words.

By being more mindful of how we use generative AI and making an effort to write with clarity and originality, we can avoid falling into the AI style trap.

In the end, writing should be about expressing your ideas in your own way. While ChatGPT can help, it’s up to each of us to make sure we’re saying what we really want to – and not what an AI tool tells us to.